- English

- Español

Media Center

Feature

Adopts American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

50 Million People in the Americas Self-Define as Indigenous.

June 15, 2016

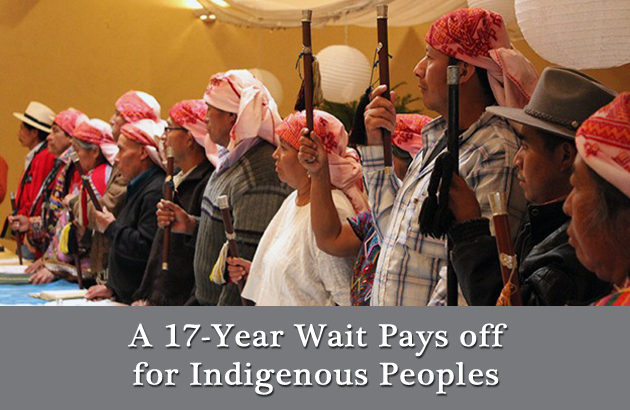

When Héctor Huertas attended the first meeting to draft an American declaration on indigenous peoples in 1999, he thought the end was not far off. Neither he, nor anyone else in that room in Washington, D.C., imagined that the end was 17 years away.

That train finally reached its destination today at the General Assembly of the Organization of American States in Santo Domingo, where the member states adopted the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by acclamation.

The declaration is the first instrument in the history of the OAS to promote and protect the rights of the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Huertas, a Panamanian lawyer and indigenous leader who belongs to the Guna people, took part not only in the inaugural meeting, but in the entire process that lasted the best part of two decades. Hence his visible satisfaction as he stood up today to address the General Assembly following the Declaration’s adoption. “Today the OAS is honoring an historical debt to indigenous peoples by acknowledging the rights of the more than 50 million indigenous men, women, and children who live in the Americas,” he said.

“The OAS has honored an historical debt to indigenous peoples from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego.”

Huertas stressed that the Declaration introduces a new framework for relations between states and indigenous peoples, including greater respect for their human rights and their consideration on topics such as sustainable development.

The Declaration also makes profound changes within states that paves the way for genuine democracy and participation for indigenous peoples in each state. It recognizes the rights to self-determination, land, resources, and, above all, free and informed prior consent,” he said.

“The OAS is ushering a new phase in relations with an instrument that could give indigenous peoples a say in all aspects of development in the Hemisphere. We are even going to ask the OAS to let us participate as indigenous peoples and not as civil society,” Huertas added.

“Historic Milestone for the Americas”

“The Declaration recognizes our right to self-determination.”

Adelfo Regino Montes, an indigenous Mexican lawyer from the Mixe people of Oaxaca, was also in Santo Domingo, where this “historic milestone for the Americas,” as he put it, was reached.

Regino Montes said that the Declaration represents a stride forward in terms of both individual and collective rights as it recognizes fundamental rights, including “self-determination and autonomy and land rights, which is very important because in countries like Mexico and Brazil the forests have been preserved thanks to the indigenous peoples.”

The representative of the Mixe people considered it valuable that the Declaration includes the issue of “free, prior consent,” which compels states to inform indigenous peoples about infrastructure and development projects before they start. “It is important that the Declaration recognizes that the indigenous people who may be affected must be consulted before any administrative or legislative steps are taken. Unfortunately, in the past our peoples have had to suffer having projects imposed on them,” he added.

The Declaration recognizes:

- The collective organization and multicultural and multilingual character of indigenous peoples.

- The self-identification of people who consider themselves indigenous.

- Special protection for peoples in voluntary isolation or initial contact, such as certain peoples of the Amazon, which is an aspect that distinguishes it from other similar initiatives.

- That progress in promoting and effectively protecting the rights of the indigenous peoples of the Americas is a priority for the OAS.

Collective rights

Foreign Minister of Bolivia (first from the left): “We celebrate the fact that in the Dominican Republic the OAS Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was adopted.”

The Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bolivia, David Choquehuanca, emphasized that the Declaration recognizes “all rights: not only human rights—which are individual—but also collective rights, such as economic, social, and cultural rights.” “We therefore applaud the adoption here in the Dominican Republic of this Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples of the Organization of American States,” Foreign Minister Choquehuanca added.

Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Peru celebrated the adoption of the Declaration in the plenary of the Assembly. Juan Gabriel Morales, Mexico’s Deputy Director General for Hemispheric and Security Affairs, described it as the “first hemispheric document that seeks to promote and protect the rights of the indigenous peoples of the Americas and, along with the United Nations Declaration, it is a basic instrument for the survival, dignity, and wellbeing of the indigenous peoples of our hemisphere.” Mexico’s representative continued: “The Declaration emphasizes the recognition of and respect for the rights of indigenous peoples to collective action and to their own legal, social, political, and economic systems or institutions.”

The Deputy Foreign Minister of Nicaragua, Denis Moncada, said that the adoption of the Declaration was the “historical vindication of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, who have suffered the consequences of colonialism and neocolonialism and, with that, the extermination of their populations, segregation, exclusion, and the loss of their natural habitat. ... We cannot deny the important contribution made by the indigenous people of the Americas to the multicultural and multilingual richness of our societies.”

Since the 1970s, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has maintained that for historical reasons and moral and humanitarian principles, states have a sacred commitment to provide indigenous peoples with special protection. In 1990, the Commission created the Office of the Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to attend to those peoples that are particularly exposed to human rights violations on account of their vulnerable situations and to strengthen the Commission's work in that area.

Key points of the Declaration

- Self-identification as indigenous peoples will be a fundamental criterion for determining to whom the Declaration applies.

- Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination.

- Gender equality: indigenous women have collective rights that are indispensable for their existence, wellbeing, and comprehensive development as peoples.

- Indigenous persons and communities have the right to belong to one or more indigenous peoples, in accordance with the identity, traditions, and customs of belonging of each people.

- States shall recognize fully their juridical personality, respecting their forms of organization and promoting the full exercise of the rights recognized in the Declaration.

- They have the right to maintain, express, and freely develop their cultural identity.

- They have the right to not be subjected to any form of genocide.

- They have the right not to be subject to racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, or other related forms of intolerance.

- They have the right to their own cultural identity and integrity and to their cultural heritage.

- They have the right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal affairs.

- Indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation or initial contact have the right to remain in that condition and to live freely and in accordance with their cultures.

- They have the rights and guarantees recognized in national and international labor law.

- They have the right to the lands, territories, and resources that they have traditionally owned, occupied, used, or acquired.

Reference: E-075/16